Overview:

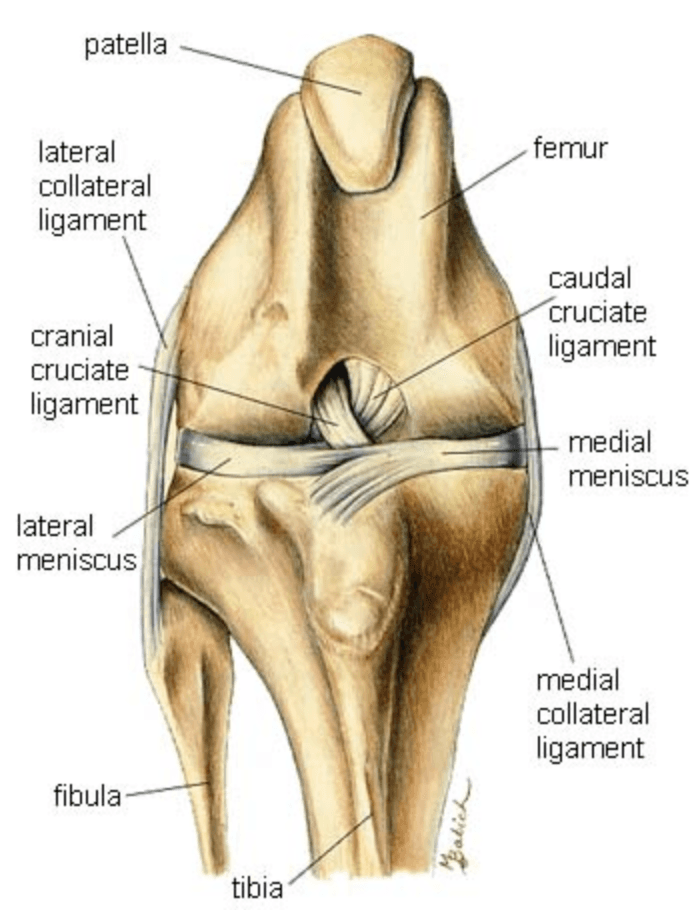

The Cranial Cruciate Ligament (CrCL) is equivalent to the Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) in humans.

It plays a vital role in stabilizing the knee by preventing the tibia from moving forward relative to the femur, limiting internal rotation, and preventing hyperextension of the knee.

A rupture of the CrCL (CrCLR) is one of the most common causes of hindlimb lameness in dogs. This can occur from a sudden “athletic” injury or from gradual, degenerative weakening of the ligament over time - often a combination of both. The degenerative form is influenced by multiple factors such as age, weight, body condition, genetics, and conformation.

Dogs with a CrCLR often show signs such as:

difficulty rising or jumping on furniture

stiffness after resting

reduced activity

lameness following play

discomfort when the knee is manipulated

Some pets may seem only mildly affected at first, while others show sudden, severe lameness. Because dogs tend to be stoic, even subtle limping indicates discomfort.

Diagnosis:

Diagnosis can be made from physical examination alone but medical history and X-rays help to confirm the suspicion.

On exam, the veterinarian looks for abnormal forward movement of the tibia relative to the femur (known as cranial drawer or tibial thrust), which confirms damage to the ligament.

In partial tears, this motion may not be obvious, but pain on extension of the knee often helps identify the injury.

Treatment:

Options include surgical or non-surgical management.

Non-surgical management includes maintaining a lean body weight, restricting high-impact activity, using pain medications as needed, and providing joint supplements (glucosamine/chondroitin and omega-3s).

Some dogs, like some people, can tolerate a cruciate deficient stifle. However, there will always be some degree of disability and you should expect a change to your pet's lifestyle.

Surgery is generally recommended, as it is the only way to restore stability to the knee.

At WCVS, we offer two primary surgical options: TPLO and LFTS

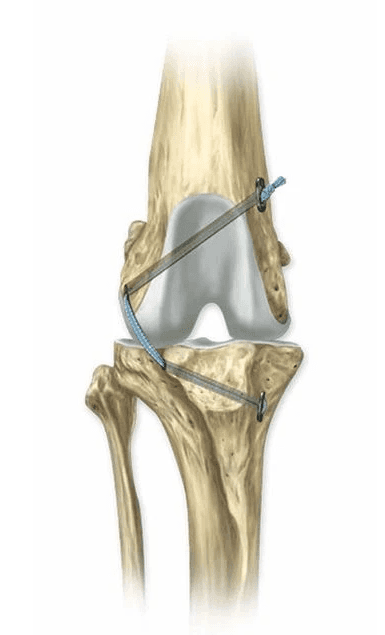

Tibial Plateau Leveling Osteotomy (TPLO):

This procedure aims to stabilize the knee by changing the biomechanics. It involves making a semicircular cut in the tibia then rotating the piece so the angle between the femur and tibia is nearly level. This eliminates the need for the CrCL and restores stability.

Conceptually, you can think of this like a 'wagon on a hill'. The wagon will remain in place with a rope tether (CrCL). However, if that is cut, then the wagon will roll down the hill. Following the TPLO, the 'wagon' sits on a flat surface, eliminating the abnormal movement.

The fragments are then stabilized with a bone plate and screws. The bone typically heals in 6–10 weeks, during which strict activity restriction is essential.

Lateral Fabellotibial Suture (LFTS):

This technique uses a heavy-duty suture placed outside the joint to mimic the ligament’s function while scar tissue develops to provide long-term stability.

The scar tissue takes at least 6–8 weeks to mature, and during this time, movement must be carefully restricted to prevent implant stretching or breakage.

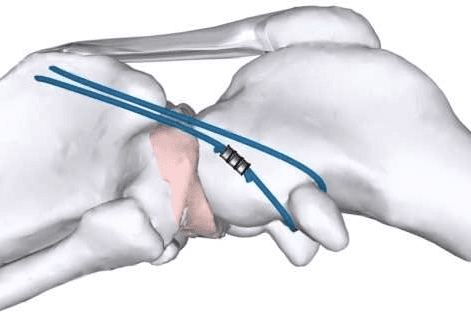

Tight Rope

This technique is similar to the LFTS in that a heavy-duty suture is placed outside the joint to mimic the ligament’s function. The major differences are the suture material used in the Tight Rope is significantly stronger which is then secured with additional metal implants.

The Tight Rope is used in dogs too large for an LFTS. Recovery time is 8-10 weeks.

Your surgeon will discuss the most appropriate option for your pet based on size, lifestyle, and overall health. The TPLO tends to yield superior outcomes, especially in dogs over 40 pounds or those with active lifestyles. The LFTS is often preferred for smaller, older, or lower-energy dogs and cats.

Prognosis and Outcome:

With proper postoperative care, prognosis is excellent—about 90–95% of patients return to normal activity. While arthritis will still develop over time, surgery helps slow its progression.

Complications such as infection (<3%) or implant issues (<0.1%) are rare, especially when incision care and activity restrictions are followed carefully.

It’s important to note that because CrCLR is often degenerative and influenced by genetics, there is roughly a 50% chance your dog may develop a similar injury in the opposite knee within two years. Maintaining a lean body weight and good muscle tone can help reduce this risk.