Hip Dysplasia

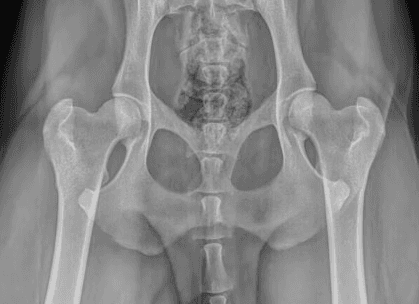

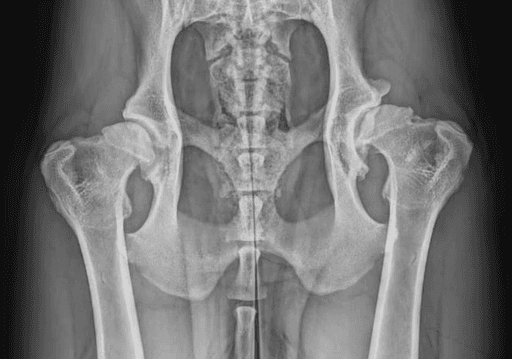

Canine Hip Dysplasia (CHD) is one of the most common causes of hindlimb lameness in dogs,

with genetics playing a major role in its development. The condition begins during early growth when there is laxity (looseness) in the hip joint.

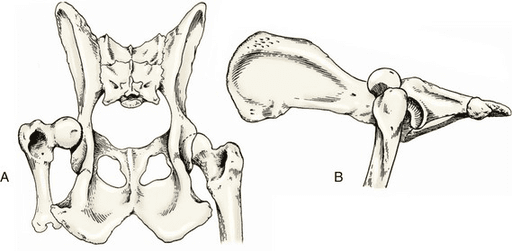

Normally, the femoral head (ball) fits snugly within the acetabulum (socket), allowing smooth motion and even joint development. When the joint is too loose, abnormal forces lead to uneven growth of the bones, stretching of the joint capsule, asymmetric cartilage wear, and bone remodeling. Over time, these changes result in cartilage loss, scar tissue formation, and the development of bone spurs (osteophytes).

Common Signs of Hip Dysplasia:

lameness following play

reduced activity

difficulty or reluctance rising or jumping

stiffness after resting

shifting weight from the hindlimbs to the forelimbs

loss of muscle mass in the hindlimbs

discomfort when the hips are manipulated

The severity of signs varies widely—some dogs show only mild stiffness as they age, while others may have significant pain as early as 6 months of age. Many young dogs experience intermittent signs that temporarily improve as the joint develops scar tissue, only to recur later as arthritis progresses.

Diagnosis:

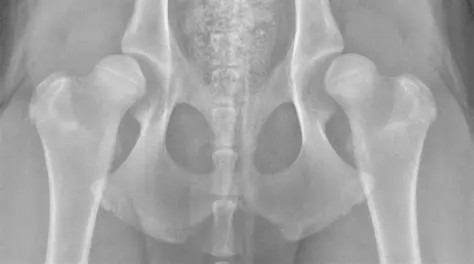

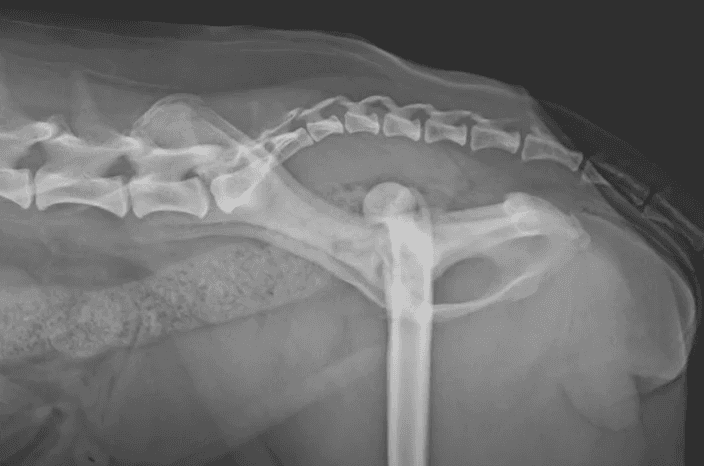

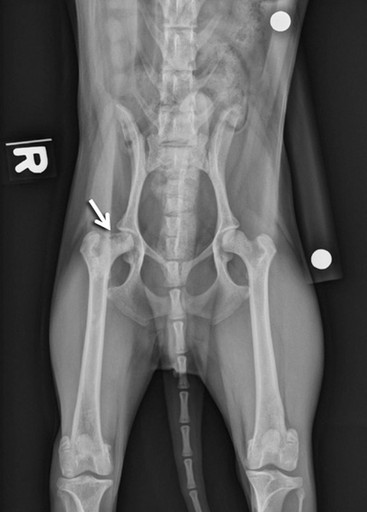

Diagnosis involves a combination of history, physical examination, and pelvic X-rays.

In young dogs, hip laxity can be detected with an Ortolani test, though false negatives can occur. As dogs mature, this test becomes harder to elicit and often requires sedation. Standard X-rays are the most common tool to identify hip dysplasia, but visible changes may not appear until a dog is over a year old. The PennHIP distraction x-ray view, performed under sedation, provides the most accurate early detection of hip laxity and can be done as early as 4 months of age.

Most dogs will begin showing signs of CHD when radiographic changes are evident. However, it will be important to determine if the signs are associated with hip dysplasia or another problem. It is very common that an acute worsening of signs in dogs with hip dysplasia is due to a cranial cruciate rupture.

Treatment:

Options include surgical or non-surgical management.

Most dogs will do well with non-surgical, conservative management alone. However, surgery is indicated in more severely affected dogs or when we want to maximize functional outcome.

Conservative management is essential for all dogs with hip dysplasia, regardless of surgery, to help slow arthritis progression and maintain comfort:

Strict weight management to limit amount of force going through the joints

Consistent Low-impact exercise to maintain a solid base level of muscle

Limit High-impact exercise to limit damage to the elbows and other joints

Rehabilitation therapy to maintain strength and joint mobility

Pain management medications as needed

Nutraceutical supplementation, such as glucosamine, chondroitin, and omega-3 fatty acids

Many dogs achieve good long-term comfort and function with consistent conservative management alone.

Surgical Management:

At WCVS, we generally only perform femoral head and neck ostectomy (FHNE), but we will briefly discuss the other options below:

Juvenile Pelvic Symphysiodesis (JPS):

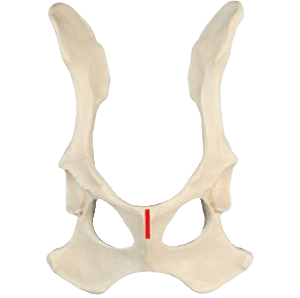

This preventive procedure must be performed at a very young age (10–18 weeks) and aims to improve hip coverage by closing part of the pubic bone growth plate.

Most puppies do not have lameness yet. Some puppies will have palpable instability, but it is difficult to predict which dogs will develop clinically relevant hip dysplasia.

For these reasons, JPS is very rarely performed.

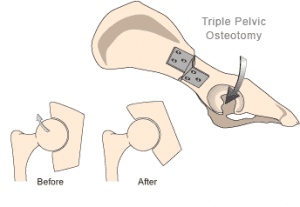

Double or Triple Pelvic Osteotomy (DPO/TPO)

These surgeries are designed for young dogs (6–12 months old) before arthritis develops but after a JPS is no longer viable. The surgeon makes controlled cuts in the pelvis to allow rotation of the acetabulum, improving the coverage of the femoral head. A specialized plate and screws stabilize the pelvis as it heals.

Similar to JPS, predicting which dogs will truly benefit can be challenging. Also, it is possible that signs of hip dysplasia and arthritis will still develop despite this procedure. For these reasons, we do not perform the DPO or TPO at WCVS.

Total Hip Replacement (THR)

THR involves replacing both the femoral head and acetabulum with prosthetic implants, similar to the procedure performed in humans. It provides the best long-term outcome by restoring normal hip function and eliminating pain.

Dogs must be fully grown (>12 months for large breeds or 18 months for giant breeds) to prevent implant shifting with growth. We typically recommend referral to NC State Veterinary Hospital, which performs a high volume of these surgeries each year.

Femoral Head and Neck Ostectomy (FHNE)

FHNE can be performed at any age and is typically reserved for dogs that have a poor response to medical management. The procedure removes the femoral head and neck, eliminating the bone-on-bone contact that causes pain. A “false joint” forms as the surrounding muscles and soft tissues take over joint function.

Postoperative rehabilitation is essential—especially in larger dogs—to achieve a good functional outcome. The goal is pain relief rather than perfect joint function, though most dogs return to a comfortable, active lifestyle with proper rehab.

Prognosis and Outcome:

Following FHNE, activity is restricted for the first 6–8 weeks. Most dogs begin showing improvement

soon after surgery, but it can take months of rehabilitation to reach their full potential. Recovery and final outcome depend on size, fitness, body condition, and commitment to postoperative rehabilitation. Structured rehabilitation usually begins 2–3 weeks after surgery and continues for several months as activity is gradually increased.

Long-term management—including maintaining a lean body weight, consistent exercise, and joint supplements—remains important for lifelong comfort and function.

Hip Luxation

Hip luxation is the dislocation of the femoral head from the acetabulum due to trauma or a fall. Significant damage to the supporting soft tissues and sometimes the bone occurs.

The dislocation is categorized based on the direction of displacement, either craniodorsal (above the pelvis) or ventral (below the pelvis). Craniodorsal luxation is by far the most common (~90% of cases) while ventral luxation is seen more often in small breed dogs. Pets with underlying hip dysplasia are at higher risk for hip luxation because of the abnormal hip conformation.

Animals with hip luxation are typically very painful and bear little to no weight on the affected limb. The leg may appear tucked under the body or rotated abnormally when standing. Over time, mild compensation may occur, but a persistent lameness will remain because of the abnormal position of the femoral head.

Diagnosis:

Diagnosis is confirmed with radiographs of the pelvis, though the condition can often be suspected based on physical examination findings.

Substantial force is required to cause a hip luxation in a normal joint, so associated injuries to the lungs, urinary tract, or other internal organs are possible. A complete physical examination and diagnostic workup are essential to identify any concurrent injuries. Bloodwork and radiographs of the chest, abdomen, pelvis, and other affected joints are often recommended.

Treatment options depend on several factors, including the time since injury, direction of luxation, presence of hip dysplasia, and patient size. In general, management can include non-surgical closed reduction, surgical reduction with stabilization, or salvage procedures such as femoral head and neck ostectomy (FHNE) or total hip replacement (THR).

Non-Surgical, Closed Reduction:

The femoral head is placed back into the acetabulum under heavy sedation or anesthesia. A supportive sling (Ehmer Sling or Hobbles) is often placed to help maintain the reduction. Slings can cause sores, fail to maintain reduction, or cannot be placed due to other injuries. Closed reduction must be performed as soon as possible—ideally within 48 hours of injury—to minimize cartilage damage and improve success rate, which is approximately 50% in early cases.

Closed reduction is not recommended in patients with hip dysplasia.

Surgical Management:

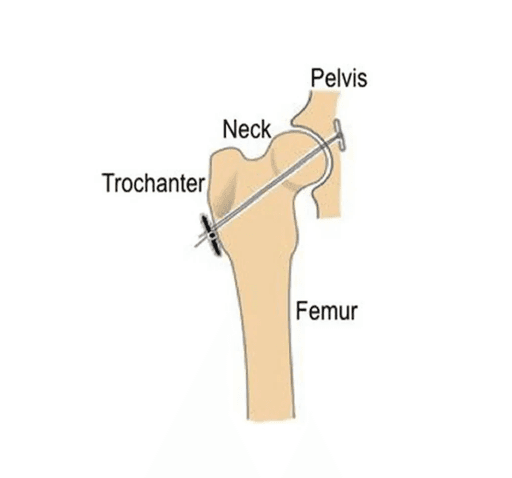

Surgical Reduction + Toggle Pin Fixation:

The femoral head is replaced into its normal position and stabilized using various techniques based on the specific patient's needs. The toggle pin fixation recreates the torn ligament of the femoral head using a heavy-duty suture passed through a small tunnel in the femoral neck. The joint capsule is then repaired and reinforced if needed.

Surgical reduction is typically not recommended in patients with hip dysplasia.

Femoral Head and Neck Ostectomy (FHNE)

Similar for severe cases of hip dysplasia, FHNE involves removal of the femoral head and neck to eliminate painful bone-on-bone contact. A “false joint” forms as surrounding muscles and soft tissues take over joint function.

Rehabilitation is critical—especially in larger dogs—to rebuild strength and coordination. The primary goal of FHNE is pain relief, though most dogs regain comfortable mobility and a good quality of life with proper rehabilitation.

Total Hip Replacement (THR)

THR replaces both the femoral head and the acetabulum with prosthetic implants, restoring normal joint function and eliminating pain. This procedure is often recommended when surgical reduction is unsuccessful or when the injury is too old to repair effectively.

We typically refer patients requiring THR to the NC State Veterinary Hospital, which performs a high volume of these advanced surgeries each year.

Your surgeon will discuss the most appropriate option for your pet based on duration since injury, patient size, lifestyle, and overall health.

Prognosis varies depending on the treatment approach.

Closed reduction offers about a 50% success rate when performed within two days of injury. It is not recommended after this timing due to poorer outcome. Strict activity restriction for four to six weeks is required to allow soft tissue healing. If articular damage is minimal and reduction is maintained, patients can recover good function, though arthritis or recurrent luxation may develop over time.

Surgical reduction has a high success rate with appropriate postoperative care. Activity must be limited for six to eight weeks, followed by a gradual return to normal activity. Most dogs recover excellent mobility, though complications such as implant failure, recurrent luxation (up to 10%), infection, or arthritis are possible.

For FHNE, activity is restricted for six to eight weeks. Rehabilitation begins at two weeks post-op and continues for several months. Outcome depends on patient size, concurrent injuries, and consistency with rehabilitation. Small and medium-sized pets typically achieve very good comfort and mobility, while larger dogs can also do well with diligent rehabilitation and long-term conditioning.

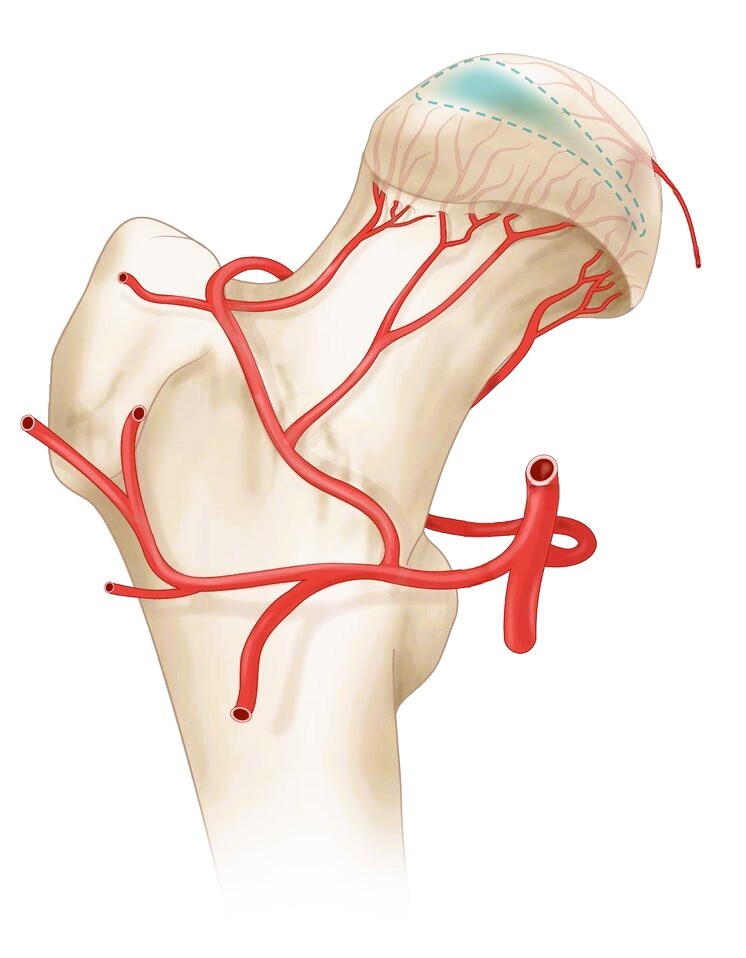

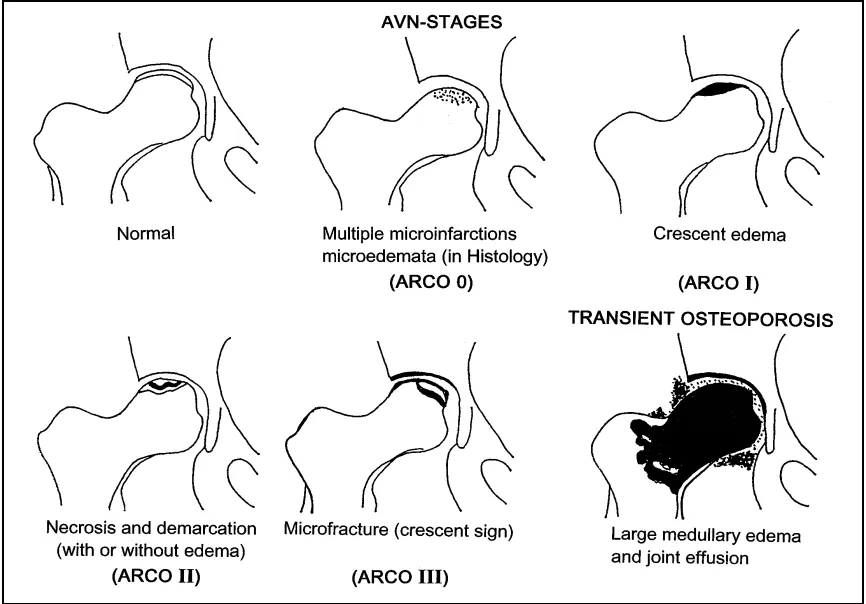

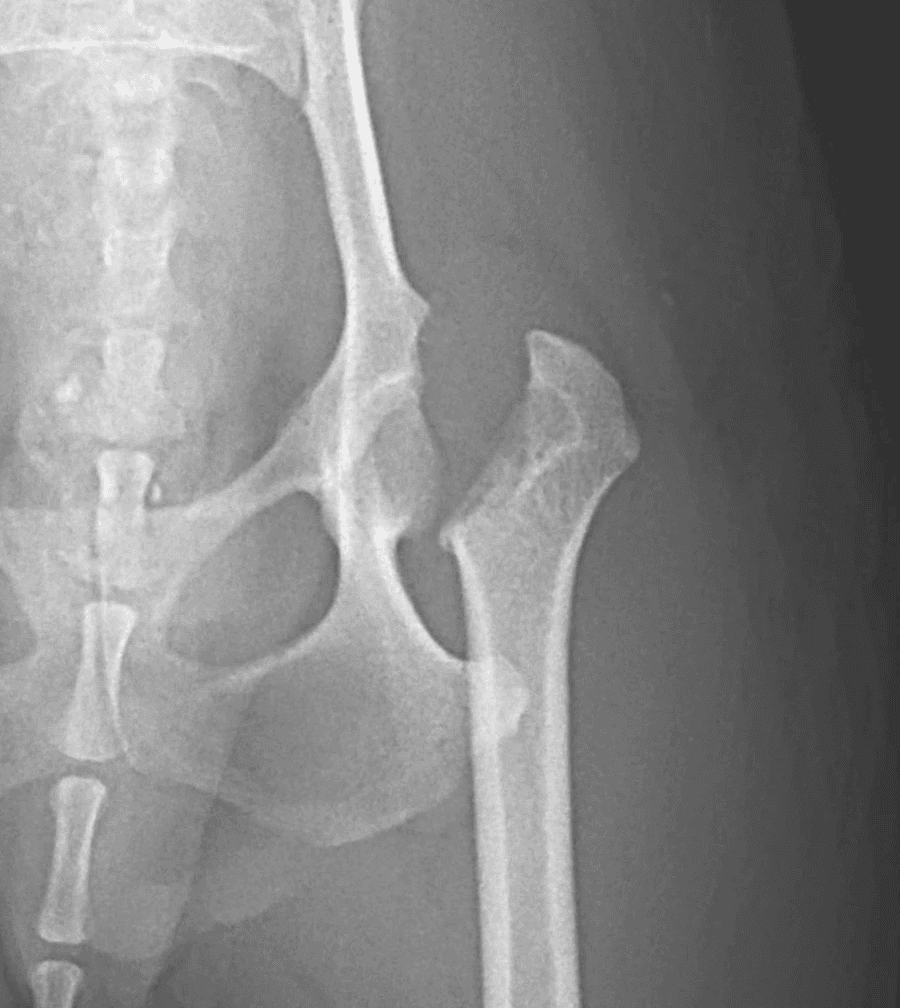

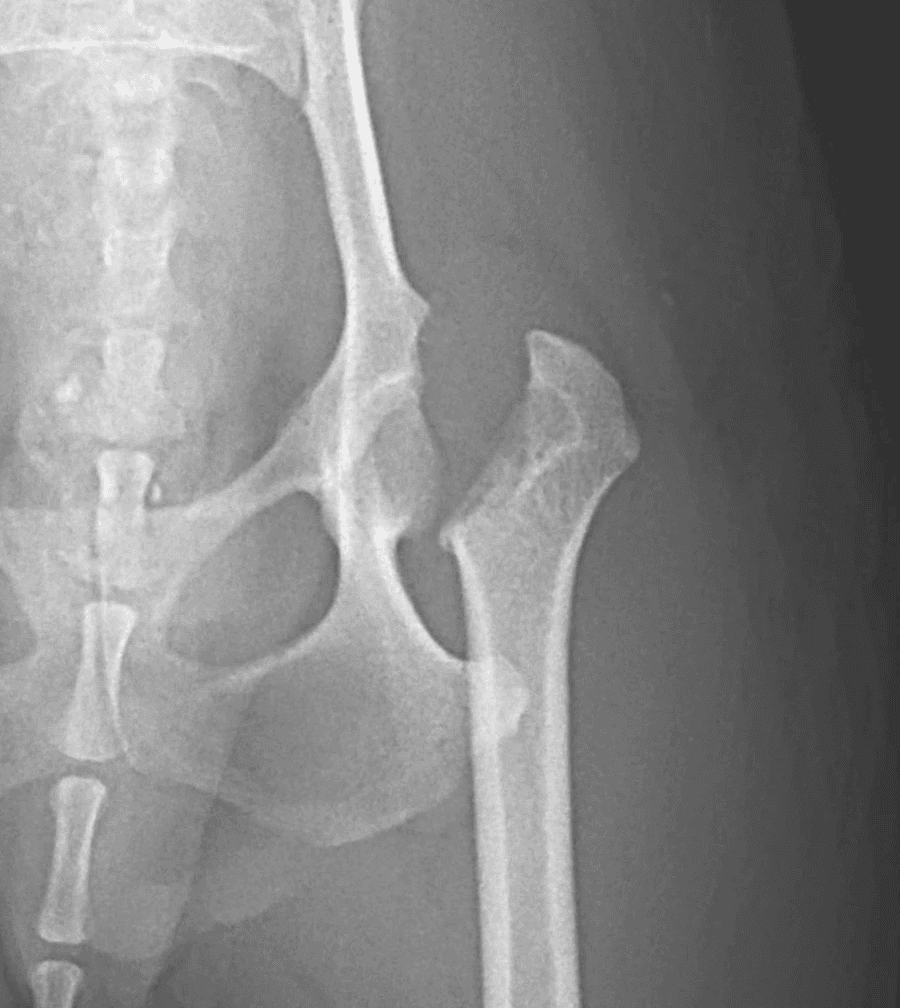

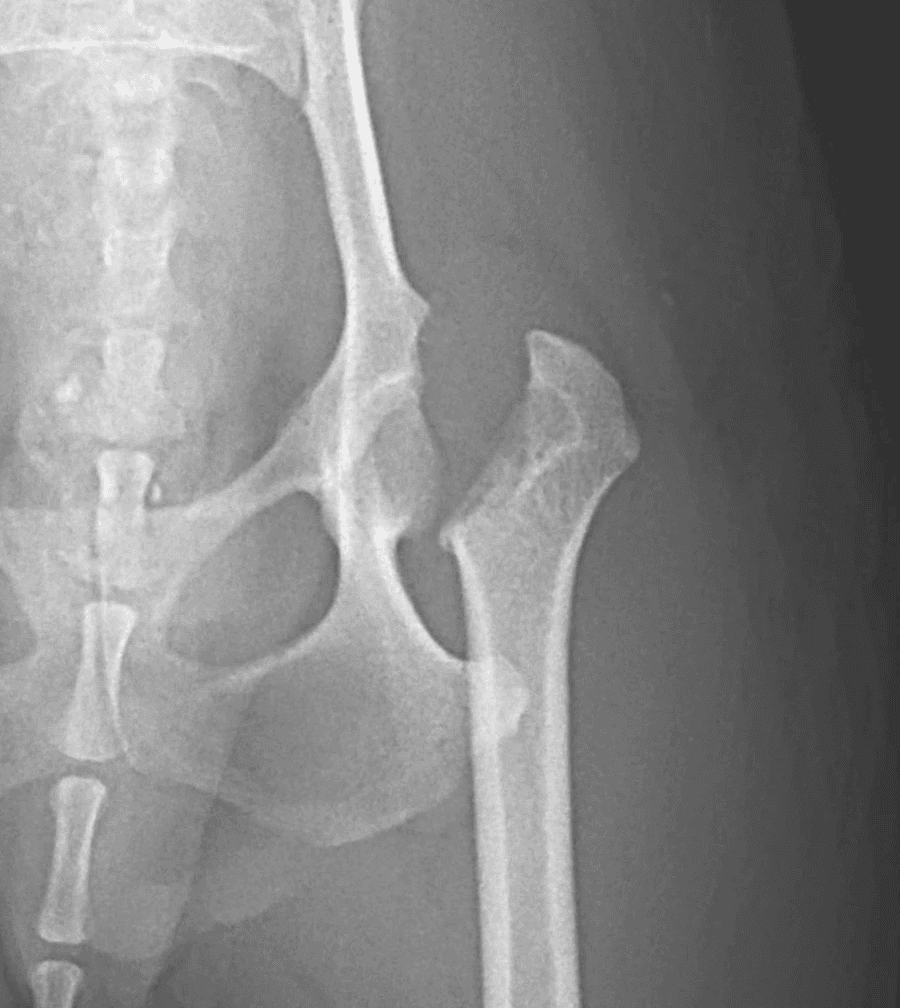

Avascular Necrosis

Avascular necrosis of the femoral head, also known as Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease in humans, is a condition in which the blood supply to the femoral head and neck becomes compromised. Without adequate blood flow, the bone tissue deteriorates (necrosis), leading to collapse and deformity of the femoral head. This process results in chronic pain and progressive loss of hip function.

The condition most commonly affects very young, small breed dogs. Early signs often include a mild but persistent hindlimb lameness that gradually worsens over time. In some cases, the lameness may become suddenly severe if a fracture develops within the femoral head or neck as the bone weakens.

Diagnosis:

Diagnosis is made with radiographs of the pelvis and hips that show the characteristic bone loss or deformity of the femoral head.

Both hips can be affected so it is important to assess both sides carefully

Surgical treatment is strongly recommended because the affected area causes pain and could potentially fracture. Healing is unlikely and painful femoral head will not heal or regain normal shape.

At WCVS, we perform femoral head and neck ostectomy (FHNE) for this condition. However, there are some surgeons that will recommend a total hip replacement (THR)

Femoral Head and Neck Ostectomy (FHNE)

FHNE involves removal of the femoral head and neck to eliminate the painful, abnormal area of bone. A “false joint” forms as surrounding muscles and soft tissues take over joint function.

Rehabilitation is critical—especially in larger dogs—to rebuild strength and coordination. The primary goal of FHNE is pain relief, though most dogs regain comfortable mobility and a good quality of life with proper rehabilitation.

Total Hip Replacement (THR)

THR replaces both the femoral head and the acetabulum with prosthetic implants, restoring normal joint function and eliminating pain.

This procedure is uncommon for avascular necrosis of the femoral head because it typically affects small breed dogs. It will also require the patient to wait until they are skeletally mature (10-12months old).

We typically refer patients requiring THR to the NC State Veterinary Hospital, which performs a high volume of these advanced surgeries each year.

Following FHNE, activity is restricted for the first 6–8 weeks. Most dogs begin showing improvement

soon after surgery, but it can take months of rehabilitation to reach their full potential. Recovery and final outcome depend on size, fitness, body condition, and commitment to postoperative rehabilitation. Structured rehabilitation usually begins 2–3 weeks after surgery and continues for several months as activity is gradually increased.

Most affected dogs are small breeds and have an excellent long-term outcome following FHNE. With appropriate postoperative rehabilitation, patients typically regain comfortable mobility and return to an active, pain-free lifestyle. Long-term management—including maintaining a lean body weight, consistent exercise, and joint supplements—remains important for lifelong comfort and function.